Long-time ACOR scholar, frequent ACOR fellow, and leading prehistorian Dr. Gary Rollefson writes below about his current research in the eastern desert of Jordan. An ACOR Video Lecture by Dr. Rollefson expanding on this topic is also available here.

Publication of the results of the ‘Ain Ghazal excavations is still a continuing process, but after excavations ended in 1998, attention switched to other aspects of prehistoric exploitation of the North Arabian peninsula in the 7th – 5th millennia BC. Much of prehistoric Jordan remained unexplored in 1998, although there were tantalizing hints of dramatic developments in areas outside of the urban extent of Amman where ‘Ain Ghazal was located.

One of the astounding developments of ‘Ain Ghazal was the abrupt decline of the population. With an estimated number of 3,000-4,000 people at 7000 BC, the settlement crumbled to a level 90% smaller, leaving the question of what happened to the people who were forced to leave the town (and others throughout the highlands of Jordan). There is little evidence that a mass migration left highland Jordan to Syria in the north or to Saudi Arabia in the southern direction, which leaves little option except for a probable movement into the eastern areas of the Levant.

SUPPORT THE ACOR FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM – Donate to the ACOR Annual Fund

ACOR is proud of the innovative scholarship that the ACOR fellowship program supports. Help ensure that future scholars will be able to enjoy the support of ACOR in Jordan by donating to the ACOR Annual Fund today.

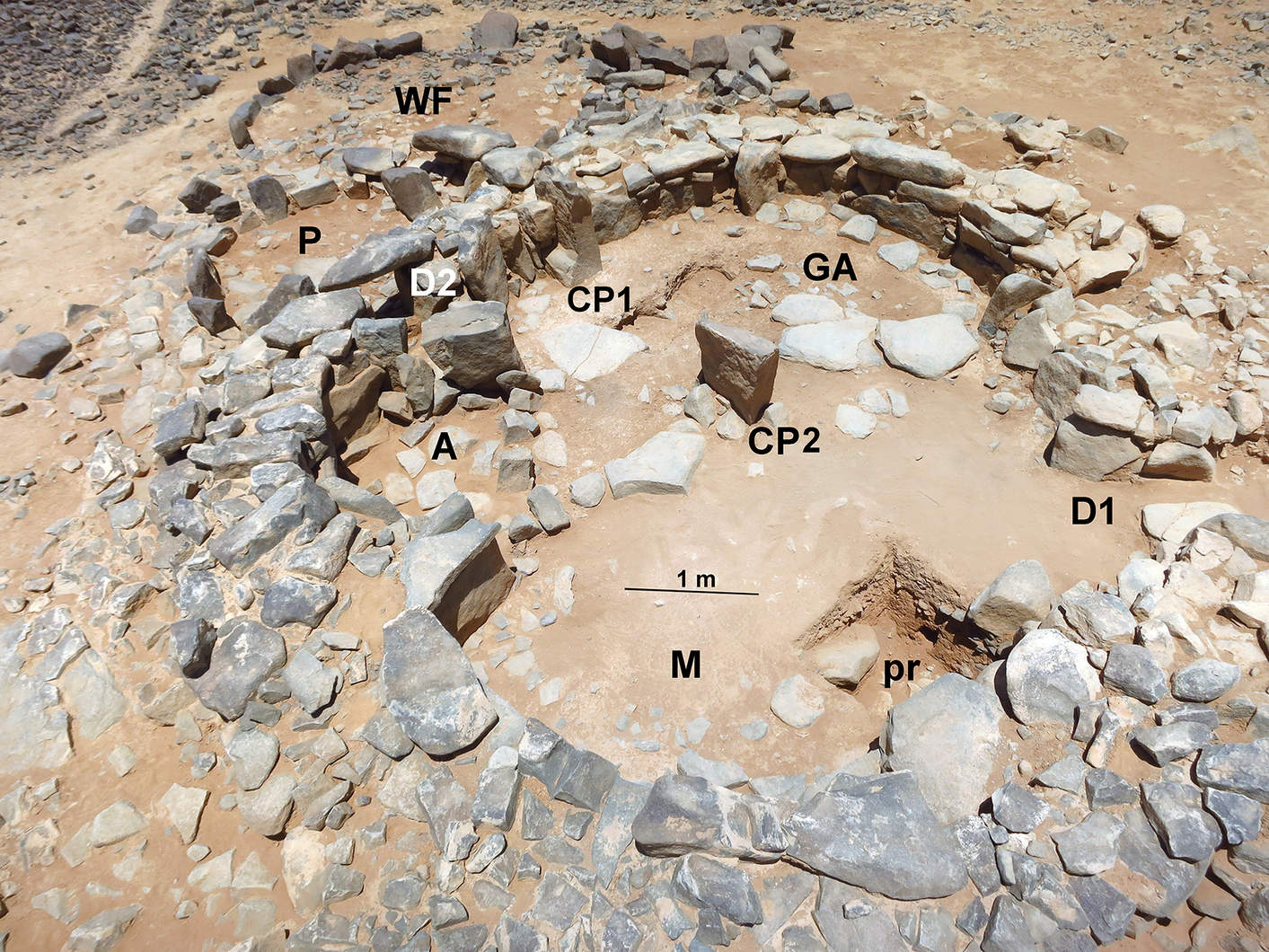

The eastern deserts of Syria and Jordan are virtually inhospitable today except for the most intrepid Bedouin, but the basalt fields of eastern Jordan (the “Black Desert”) have exuberant evidence of intensive exploitation of the region. Two areas, one on the eastern fringe of the Black Desert and the other on the western edge, are rife with villages of semi-permanent residential structures that reflect continued returns to the same sites. Even though it is unlikely that agriculture could have been practiced except on the most opportunistic occasions, our excavations at Wisad Pools and in Wadi al-Qattafi indicate that some of the refugees from ‘Ain Ghazal and other western farming villages set up seasonal settlements in the Black Desert where people stayed with their herds of sheep and goats, heavily relying on the hunting of abundant gazelle herds for meat, but also sustaining themselves on caprine dairy products.

The basalt-capped mesas of Wadi al-Qattafi and the plain of the Wisad Pools each include hundreds and hundreds of residential and ritual structures (the latter including burial towers and mounds). So far, our excavations have investigated only residential structures that date to the Late Neolithic period (c. 6500-5000 BC), which fits nicely with the depopulation of permanent settlements in the west (such as ‘Ain Ghazal). But when one considers the Stygian environment of the Black Desert today, where even after the rainy season there is almost no vegetational cover development at all, one must ask, “Why are there so may permanent structures in the Black Desert during this period?” The answer becomes simple based on the archaeological evidence.

Beneath two houses our excavations revealed an ancient soil that had been protected from later wind erosion, a soil that absorbed rainfall, providing a reservoir for vegetation growth that was lush (and providing ample pasturage for herds of sheep and goats). Charcoal has provided evidence of oak trees in the region, as well as the presence of figs, both of which strongly indicate a much higher rainfall during the Late Neolithic period. The barren landscape of today was in essence a grassland that supported not only large populations of wild animals, but also the greedy appetite of domesticated sheep and goats.

Several more seasons of excavation at both sites will explore variations in architecture and their implications for changes in social organization, subsistence economy, and ritual behavior in these previously under-explored parts of the Levant.

Research in the Black Desert is being conducted by the author, Dr. Yorke Rowan (U. Chicago-Oriental Institute), and Dr. Alexander Wasse (U. East Anglia), with substantial input by Dr. Morag Kersel (DePaul U.), Dr. A.C. Hill (Dartmouth College), Dr. B. Lorentzen (Cornell U.), and Dr. J. Ramsay (SUNY Brockport). The investigations are heavily supported by the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR), Amman.

Financial contributions from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Geographic Society were instrumental in providing the means of investigating the exciting cultural developments at Neolithic ‘Ain Ghazal, which brought to light some of the most stunning examples of ritual behavior in the Levant during the 8th and 7th millennia BC.

Written by Dr. Gary Rollefson

Gary Rollefson is Professor of Anthropology at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington. He is a specialist in the archaeology and peoples of the prehistoric Near East who, together with Jordanian archaeologist Zeidan Kafafi, is well known for the excavation of the important Neolithic site of ‘Ain Ghazal, where some of the world’s oldest statues were discovered. Rollefson studied anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley (BA, 1965) and then at the University of Arizona (MA, 1972; Ph.D., 1978).

Gary Rollefson is Professor of Anthropology at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington. He is a specialist in the archaeology and peoples of the prehistoric Near East who, together with Jordanian archaeologist Zeidan Kafafi, is well known for the excavation of the important Neolithic site of ‘Ain Ghazal, where some of the world’s oldest statues were discovered. Rollefson studied anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley (BA, 1965) and then at the University of Arizona (MA, 1972; Ph.D., 1978).